Using Art to train judgement for complex decisions: reflections from Vienna

Why Art matters for decision-making in complex environments

Maybe we can all agree there is a point at which more information stops being helpful. Mainly because more information often means more facts, more data points, more references and not necessarily more insight which can meaningfully help us move forward.

For people accustomed to operating at a high level, where decisions carry financial, reputational, and long-term consequences, the real challenge often ends up being deduction, judgement and selection; what to decide and what would be the impact?

Even from a personal stand point you may reach a crossroad, or inversely are stuck on an endless road with no turning in sight; what must you do to continue progressing? Or more precisely yet, what must you do to continue progressing which will lead to a desired outcome, vs progression for the sake of progression which doesn’t lead to many places at all.

When outcomes unfold slowly and certainty is impossible, the question becomes: How do I know this is worth pursuing? And from a commercial lense; how do we differentiate ourselves at a time where there is a mass commoditisation of capabilities and unprecedented saturation.

These concerns are rarely voiced, yet sit beneath many high-stake choices. Surrounded by expertise, opinion, and constant analysis, it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish a brand and a service, let alone build impactful momentum.

Art, when approached properly, offers an unexpected way to deal with complexity. It is one of the few remaining environments where judgement can be trained without consequence.

It is not a coincidence that there has always been an interplay between Art and capital, Art and high performing, highly ambitious people. There is much to be said about a certain slice of society and its relationship with the arts has been beneficial both socially and financially.

The elevation Art provides in a relaxed context, directly translates to the elevation needed in a commercial context. Being able to aptly identify the sentiment of a piece is no different from being able to aptly read the boardroom.

Patience allows for ideas to converge

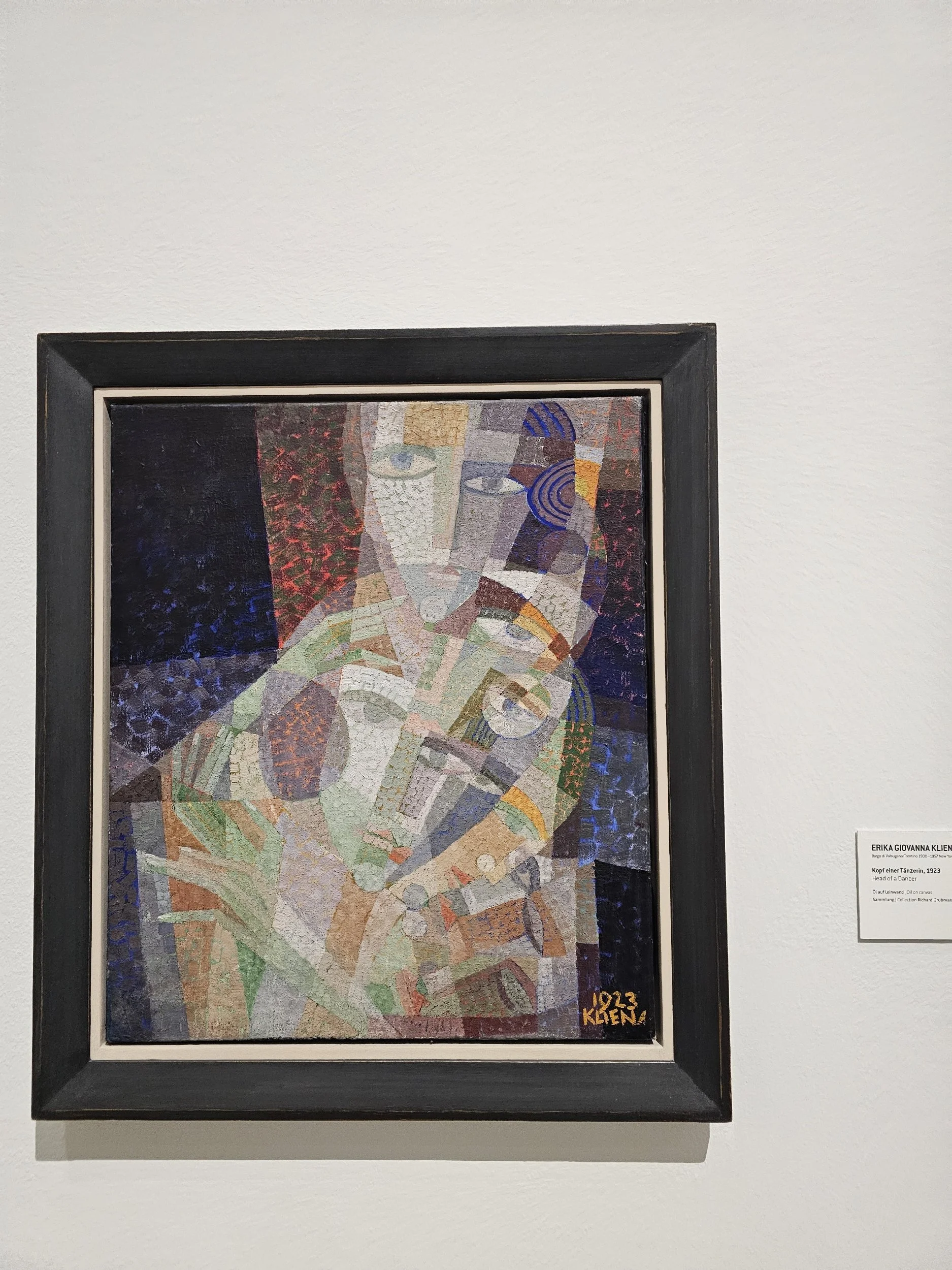

Most people assume that the challenge with Art is understanding it; maybe it’s intimidating, irrelevant or just not of an interest. But when looking at it with new eyes, we find that another challenge is really to do with how quickly the mind wants to decide and how long it is able to linger, before it glazes over or collapses into insecurity.

In a binary ecosystem we are conditioned to move from perception to conclusion almost instantly: like or dislike, good or bad, relevant or irrelevant. This habit is efficient in fast-moving environments, but it weakens judgement in complex ones because simplifying complexity requires identifying nuances, identifying patterns, embedding context and searching for connection.

Art can disrupt this speed reflex and slow the interval between seeing and deciding to allow the emergence of details which are often skipped over. Over time, learning to remain present with a work without rushing to judge, or even rushing to move on and consume the next piece (as per our current scrolling era), strengthens our ability to wait, endure and assess.

If you’re self aware enough, you begin to notice not only the artwork, but the mechanics of your own decision-making: where impatience arises, where assumptions fill gaps, where external cues substitute for your internal voice, and most interestingly… what you decide to overlook and what you decide to stay focused on. In this respect not only does your experience start enabling the development of personal taste, but also of self awareness.

Emotional ambiguity sharpens discernment

Much of modern life exploits our need to want clarity and belonging, in order to influence how we act and feel.

When you refrain from reacting or deciding and grapple with what to make of something, you’re forced to sit with uncertainty from which a different kind of emotional intelligence can emerge.This moment can be uncomfortable to some precisely because it reveals how dependent we are on speed for confidence, answers, direction and stimulation.

The beauty with all the Arts is that a productive output is not a prerequisite, which on the surface seems counterintuitive when in pursuit of a specific outcome. Not everything has to be explained or measured in order for it to still play a meaningful role, because much of the detail plays a part in contributing to the - quite literally - bigger picture.

Learning to register tone, tension held beneath the surface, meaning implied rather than declared, teaches us to hold questions without answers and in turn, teaches us to remain committed through emotional ambiguity. This can strengthen our capacity to absorb and reflect and ultimately embrace life’s tide as it waxes and wanes.

Good judgement is ultimately practiced by developing a relationship with uncertainty.

Meaning deepens impact in the real world

Contemporary culture privileges novelty; new ideas, new strategies, new narratives are often assumed to be superior. Add a powerful marketing engine and you have (what is starting to become increasingly common) ‘bubbles’ (tech, AI, bubbles) where society collectively decides to place their bets on the trend of our times.

This pursuit for progress is only impactful when there are values, purpose and vision deeply anchored in the framework of that pursuit. Anything less and you’ll fail to win hearts and create stickiness, qualities which admirable and impactful leadership require.

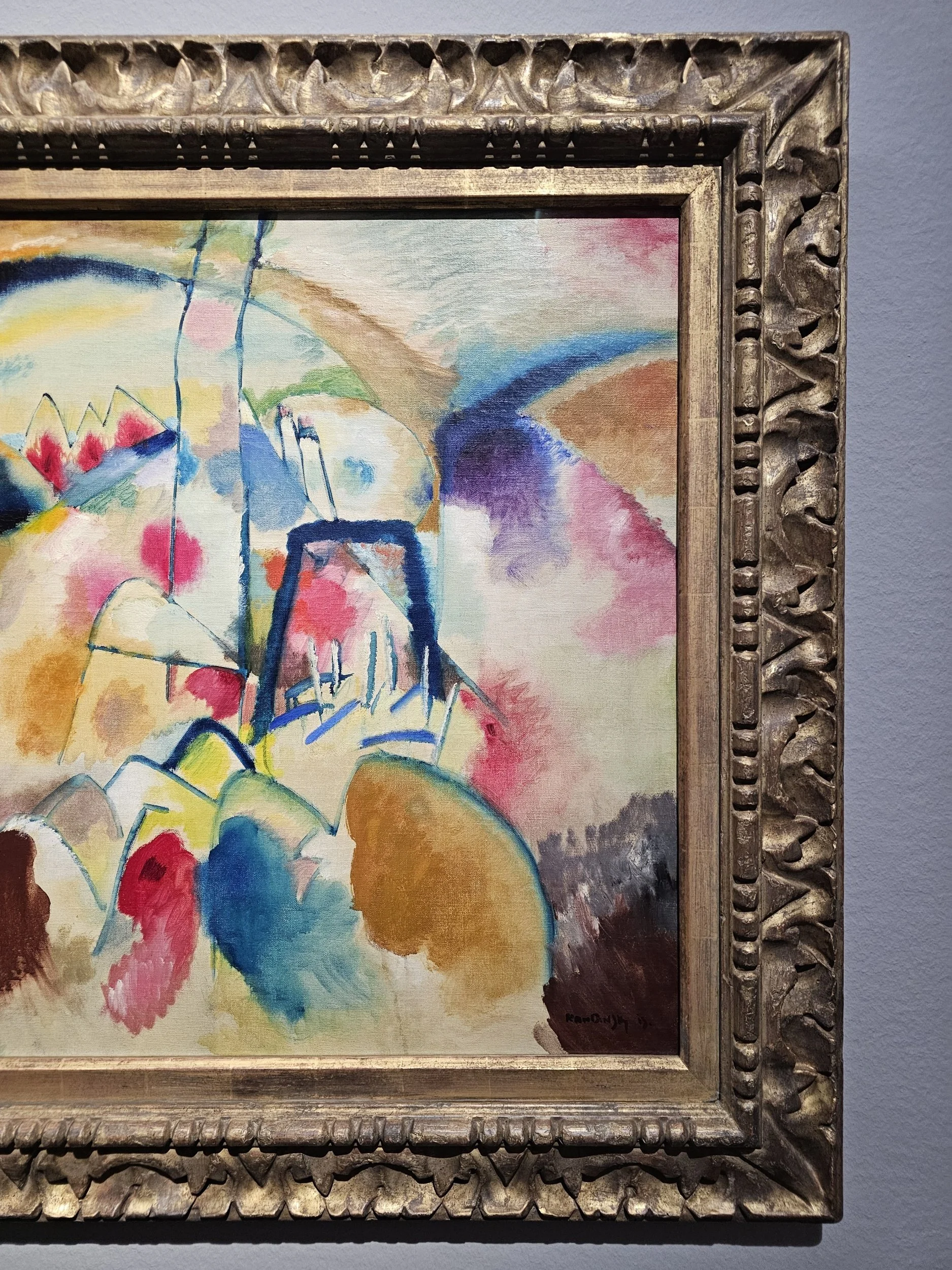

Art, particularly rooted in long traditions, shows how meaning significantly transforms an experience. Motifs repeat, themes recur, symbols reappear across time and most of all, they attempt to represent the desires and challenges of a particular point in History. Understanding accumulates slowly, through comparison and memory. Whilst viewing a piece of work doesn’t require much, to absorb it can require the context, background and insight into its story of how and why it came to be.

This is a vital lesson for anyone operating in long horizons.

Good judgement rarely comes from chasing what is new or what is laid out in front of you. It comes from listening to what was not said and seeing what has not yet been revealed.

Art hones the power to train this perceptual patience.

Small changes have big implications

Unlike much of modern society, Art does not impose a narrative, and that is even despite when it has one.

In the real world, regardless of whether cause and effect unfold instantly or gradually - they do eventually unfold to formulate two different realities (there is life before the cause, and then life after the effect of the cause).

With Art, both cause and effect reside within the viewer, mixed with our own subjective History and objective truth. As such, the unfolding ends up being our responsibility, how much, to what extent, and if at all.

If you rush, the work gives you very little. If you stay, it begins to open, gradually, proportionally to your engagement. And often you can find yourself enchanted and amazed at how simply the most complex of ideas and heavy implications are conveyed. This teaches an important psychological lesson: most decisions are a byproduct of an accumulation of factors, both external and internal, the fine balance of which resides in your hands.

For individuals accustomed to being guided or informed, this can feel unfamiliar. Yet it is precisely the lack of an imposed narrative that creates an opening for the viewer to amalgamate their internal world, and reconcile with the facts of the artwork at hand, to eventually arrive at their own conclusion.

How Vienna made this visible

A trip to Vienna made this role of Art so painstakingly obvious. There is no escaping Vienna’s imperial beauty, and how its History gave birth to such formidable values in at least two points in time:

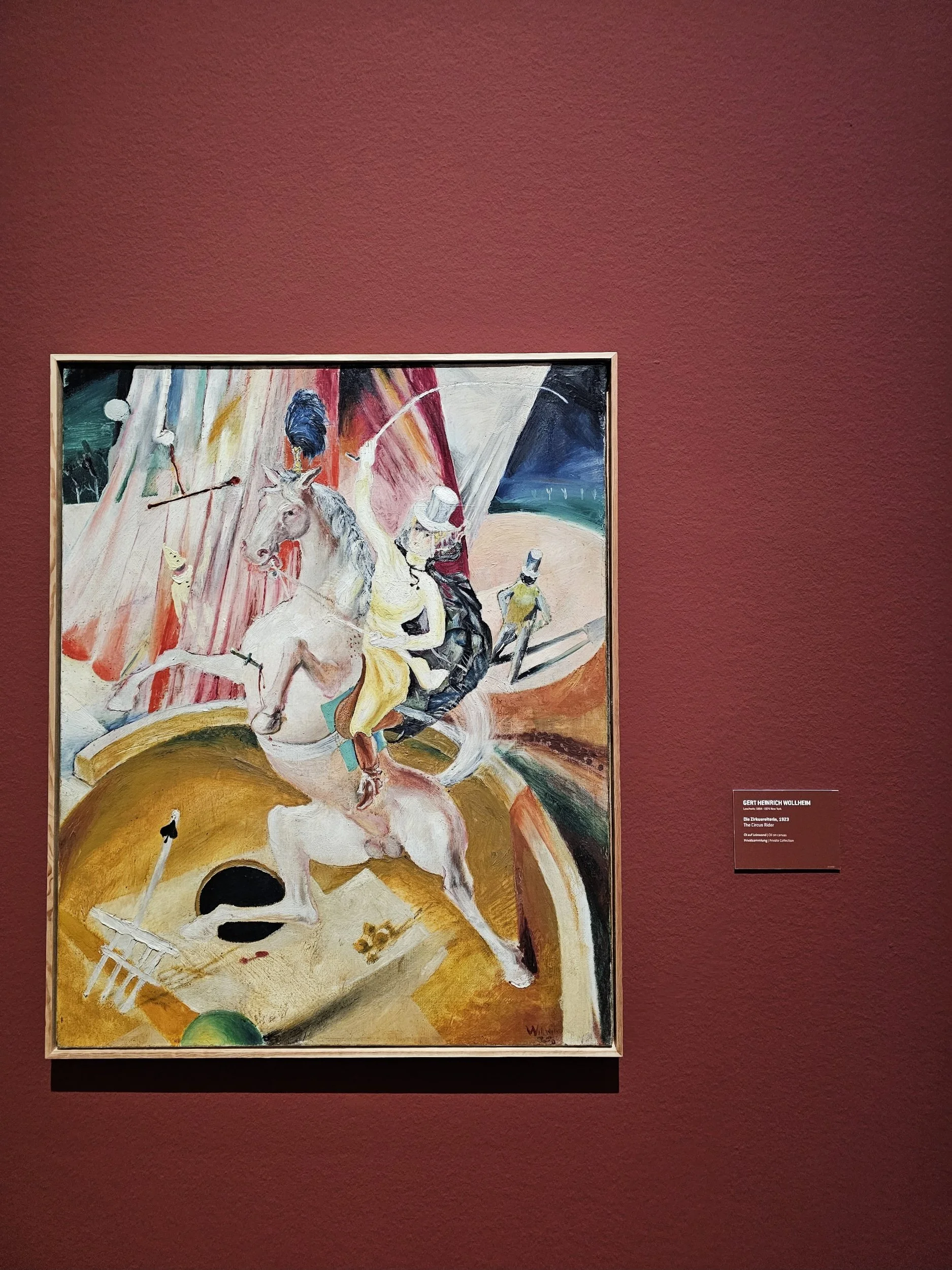

The Vienna Secession

The Vienna Secession was an artistic revolt, founded in 1897 by Austrian artist Gustav Klimt. He led a group of painters, architects, and designers who were done with Vienna’s cultural establishment. At the time, Vienna’s official art institution, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, promoted historicism conservatism and academic painting: Art that looked at the past rather than responding to modern life.

Klimt felt this was stifling innovation so withdrew, founding a new philosophy with fellow artists which was radical for its time, consisting of:

Art must be free from academic rules

Each age must have its own style of art

Art, architecture, design, and craft must be treated equal

This marked a moment in time when judgment was being shifted from having to adhere to regimented standards, to cultivating personal sensibility.

Where previously taste was expected to be inherited, due to a society upheld via a monarchy from which taste and capital moves through succession, the idea that taste could be something you could develop started to emerge. Understandably, this would shake much of institutional foundations which were built on selectivity and exclusivity.

The role of the Vienna Secession is not too dissimilar from what great leaders today must embark on: from operating within inherited frameworks, to taking responsibility for discernment when no framework fully applies. For people navigating saturated markets and an unpredictable terrain, judgment must surpass precedent and authority, and instead recognise when an old structure has exhausted itself.

Viennese Lebenskunst - ‘the Art of living’

Alongside the Secession’s, Vienna cultivated another discipline which was fast coming up against the modern world: Lebenskunst - the art of living well.

Figures such as Sigmund Freud, known as the father of psychoanalysis, would return to the same cafés daily, occupying the same tables for hours, reading, observing, and revisiting ideas without urgency. This culture normalised delay as part of intellectual labour. Whilst today this is reduced to a lifestyle, something people do for leisure and promote on social media, Lebenskunst was about changing the inherent tempo of people’s lives with the understanding that some forms of clarity cannot be summoned on demand, but emerge only when the mind is given space to wander, circle, and settle before action. This wasn’t done consciously or named explicitly, it was the natural way of processing and progressing for those seeking to pave new ways and reach new heights outside an archaic system.

In contrast to today’s bias toward immediacy, productivity and speed, Lebenskunst reminds us that clarity often emerges by creating the conditions in which insight has time to surface.

Why Art

Whilst Art can be intellectualised much, and much can be said for all the ways we can finesse our decisiveness, fundamentally the effect of Art restores something more elemental: a sense of beauty, pleasure, and inner expansion that appears, on the surface, unnecessary. And it is precisely this seeming superfluity that allows Art to reach parts of the psyche untouched by analysis alone, which reinforces self-worth, belonging and meaning. From that internal steadiness, clarity becomes possible because it strengthens the inner conditions required to meet the world with depth, proportion, and purpose.