Are we entering a modern day Renaissance? If so, how do we maintain advantage in an era of global uncertainty?

Amor Vincit Omnia by Caravaggio

In Caravaggio’s Amor Vincit Omnia, Cupid stands triumphantly amid the symbols of human achievement, instruments of knowledge, power, discipline and order scattered at his feet. The Latin title translates simply as Love Conquers All, but the provocation runs deeper than romance.

Across many interpretations, one conclusion emerges: no matter how elevated we believe ourselves to be, desire undoes us. Intellect, discipline and hierarchy doesn’t survive intact once eros enters the room.

Where earlier Renaissance thinkers believed reason could civilise appetite, beauty could refine desire and harmony reflected divine order, Caravaggio was more sceptical. His work suggests that power is unstable, morality, situational and human behaviour far less governed by rational ideals than civilisation would like to believe.

In this sense, Amor Vincit Omnia challenges the belief that society can be sustained by reason alone, even at the height of an era that prized rationality, order, and human potential.

And today, standing on the edge of another monumental shift, that tension feels newly familiar. The world we are moving through no longer feels the way it once did. People are saying things aren’t what they used to be, but even that feels insufficient. Life seems to be flattening; feels thinner, less dimensional, harder to direct yourself within. Many struggle to articulate why modern life feels empty, sensing only that something fundamental has shifted beneath the surface.

We’ve become accustomed to attributing this feeling to external forces: economic instability, fractured geopolitics, technological acceleration, the aftershocks of COVID, the rise of AI, the volatility of housing and job market. The list goes on. All of this is true, and all of it matters. But even taken together it doesn’t fully explain the atmosphere we’re living in; fatigue and compromised hope. And dare I say, the value of things have become questionable. What we are experiencing feels closer to a loss of meaning in modern life than a single economic or political cycle.

There is also a real commercial fatigue. Everything is for sale, all the time. Every moment has become an opening, every pause an opportunity to monetise attention. Even when you’re seeking something privately, it’s difficult to do so without being preached to. Private spaces, in any meaningful sense, have become rare. This persistent invasion has produced a deeper attention economy burnout, one that shapes how people think, choose, and relate.

Over the last couple of years I found myself responding to this instinctively. Walking more. Reading more. Spending time in places which are slow to stimulate, if at all. Returning, again and again to things in the real world which can help recalibrate my senses and ownership of my perspective. And I know I’m not alone with this recent ‘going analogue’ trend; more people are detaching from digital and switching off from media.

Shortly after Christmas, I took a day to walk through London as I often do to uplift my spirits. I strolled through my favorite parts of old towns from St James’s, Pall Mall, Green Park, Berkeley Square, Mount Street all the way up towards Marylebone.

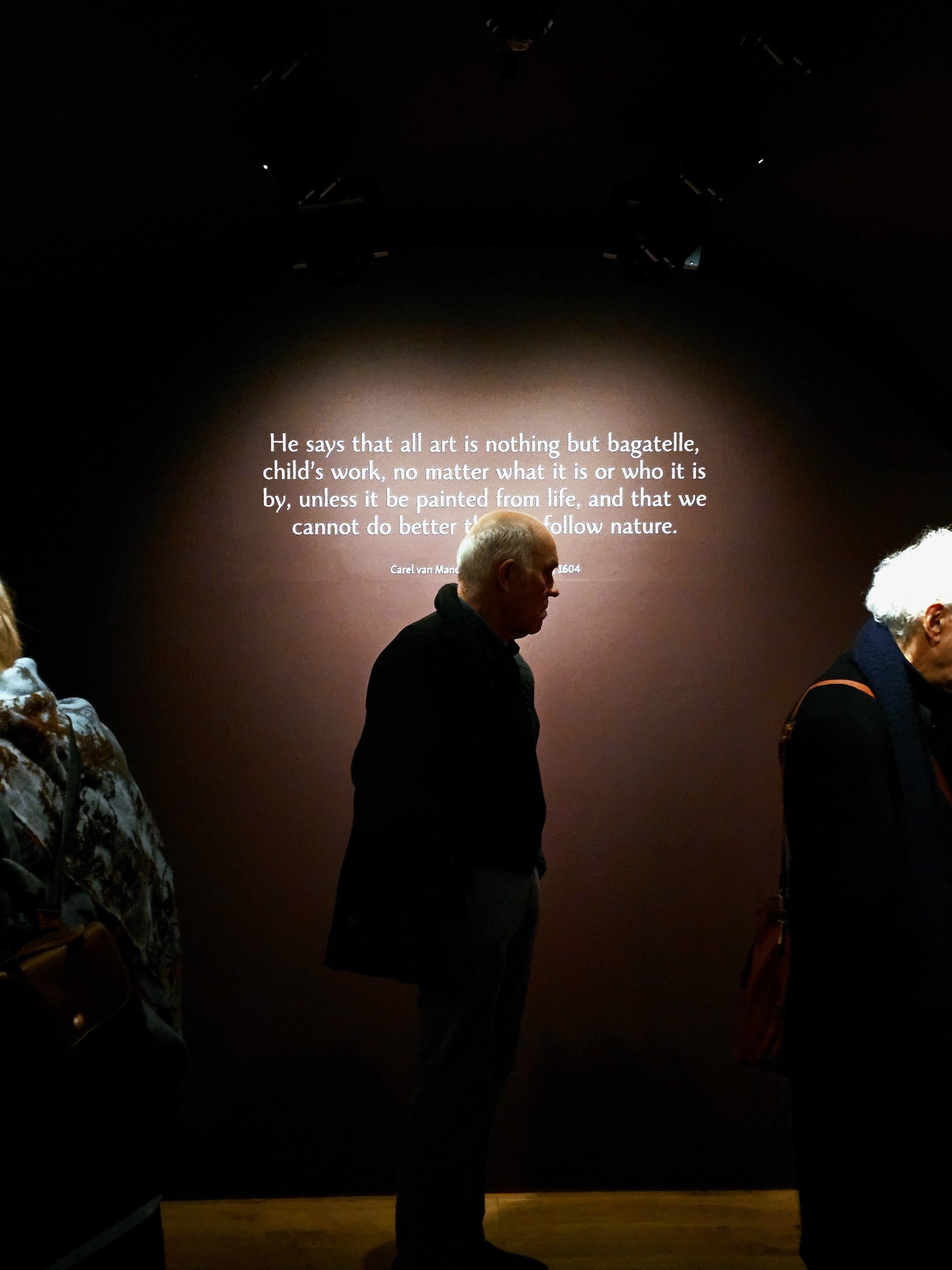

I stopped at the The Wallace Collection, where an exhibition centred on Caravaggio’s Cupid was on display. Coupled with my recent visit to Vienna and soaking in its grand, imperial legacy, this all re-alighted an unexpected affinity to the Renaissance.

I realised I wasn’t drawn to the period for its beauty alone, but for what it represented. The Renaissance emerged from collapse: after plague, after fragmentation, after the disintegration of structures. What followed was a period of reinvention, a return to core principles and renewed attention to what deserved study, patronage and care.

What often gets overlooked is that this wasn’t a local phenomenon. While Italy was rediscovering classical humanism, other civilisations were undergoing their own transformations. It was a global moment of re-assessment and rebellion.

Much of what fuelled the Renaissance had travelled long before through older, more established centres of learning. Mathematical ideas such as algebra and algorithms, developed by scholars like Al-Khwarizmi, had already reshaped how the world could be measured, calculated and understood.

Medical, astronomical and philosophical texts moved gradually from the Islamic world into Europe through trade routes, translations and contact across the Mediterranean, carrying with them a rigor of thought that Europe would later build upon.

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 under Mehmed II marked the end of the Byzantine Empire whilst reconfiguring the intellectual geography of Europe. Many Greek scholars who protected the classical texts in philosophy, mathematics, medicine, and science, left the city carrying with them manuscripts that had been preserved and studied in the Eastern Roman world for centuries.

This movement coincided with growing demand in Italian city-states for precisely this knowledge, as humanist thinkers sought original Greek sources rather than medieval Latin summaries.

The result was a sudden opening: a westward flow of texts, teachers and ideas that accelerated Europe’s re-engagement with classical learning at exactly the moment it was culturally and economically prepared to absorb it. Scholars and manuscripts migrated westward, bringing classical knowledge back into circulation just as Italian city-states were ready to receive it.

Importantly, this movement was not the result of intellectual decline; the Ottoman court itself actively advocated scholars, libraries, and translation even as knowledge circulated beyond the city’s walls.

What Europe would later call a Renaissance was, in truth, part of a wider, uneven moment of global exchange shaped by movement, disruption and the transfer of ideas across civilisations, not by a single place or people alone. Across Persia, the Middle East, and Central Asia, traditions of scholarship, architecture, and urban culture continued to thrive.

So when it comes to this period in History, the underlying series of questions really were:

What is a human?

What is worth studying?

What deserves protection?

What kind of life is worth building when certainty disappears?

When I reflect on where we are today, there are many parallels.

Truth feels contested. Institutions feel hollowed out. Hierarchies are declining. Everything is optimised, but little feels meaningful. We are saturated with information (not to mention the ramp up of repetitive AI content) yet now have even poorer judgement.

If there is a modern Renaissance unfolding, and I don’t say this lightly, it will be selective and uneven. It will take shape in how certain people choose to live, what they choose to protect and where they withdraw their attention.

Not everyone will experience this period as renewal. Historically, they never do.

The right question therefore, is not whether the world will settle, but what is this moment shaping and how is it going to divide people. There are certain people who will learn to live better despite the world not improving uniformly and learn the art of living well in uncertain times.

After all, history has shown that there is something to be made of even the darkest of times. So how should one possibly approach the current changes to ensure you don't lose ground and continue to maintain, and continue to enhance, your legacy for turbulent times?

Build your own hierarchy

When institutions lose credibility, most people lose their reference point. The minority who don’t are those who construct internal standards. You need to decide what matters before the world tells you, by having a personal hierarchy of values and not outsourcing judgement to trends or algorithms. This shows up practically as having fewer opinions but held more firmly. Slower decisions but made with certainty and a noticeable calm around urgency that isn’t real. In an era of hierarchies declining, discernment becomes a form of stability and differentiation.

Treat attention as a finite, non-renewable asset

Most people talk about time. The people who live better think and talk in terms of attention because they know constant exposure to low-grade noise produces low-grade thinking. Attention, once fragmented, is difficult to recover. So you curate what enters your mental and physical environment by choosing fewer inputs, but higher quality ones, and value spaces, objects and conversations that slow you down rather than stimulate.

Withdraw from mass optimisation

Here’s an uncomfortable truth which most people won’t say: what works at scale rarely works at depth. The people who live better stop thinking in terms of trends and maximum outputs. (Ironically, it is then people who live better who are able to scale.) Consider what will sustain you over decades and what sharpens judgement rather than dulls it. This affects how you’ll work (fewer but more meaningful and profitable engagements), how you consume (less, but better), and how you relate (smaller circles, higher trust).

Reframe culture as a capability

Exposure to depth in art, music, architecture and thought subtly conditions how one handles complexity elsewhere. Art is not decoration, beauty is not aesthetic excess and culture is not escape. These are tools that help shape a life with clearer direction and sense of purpose. For centuries, culture has functioned as a training ground for judgement, sharpening perception, patience, and the ability to sit with ambiguity without rushing to resolution. Those who consistently engage with cultural work develop a higher tolerance for complexity and a more refined sense of proportion, both of which become decisive advantages when navigating uncertainty. In this sense, culture helps informs how decisions are made, how risk is assessed, and how long-term value is recognised before it becomes obvious to the crowd.

Slow down vs accelerate

While the world accelerates, you must continue to do something counterintuitive: slow down selectively. Not everywhere, but where it matters. Build long-term relationships with places, ideas and institutions. Value legacy knowledge over constant reinvention and think in decades rather than short bursts, which the current climate has people set up for. Slowing down creates control and the space to see second- and third-order consequences that are overlooked at speed. Those who master this discipline are rarely the first to move, but they are consistently the ones still standing, and well-positioned, when the world turns.

Accept unevenness and stop waiting for recovery

This is perhaps the most psychologically liberating shift. Stop waiting for the economy to stabilise, for politics to resolve and for culture to resume as per a bygone era. Know that history does not heal uniformly. It heals selectively.

If History is any guide, moments like this reward those who relentlessly pursue. Periods of fragmentation have always elevated a certain kind of person, not the loudest, nor the most reactive, but those capable of holding standards when others abandon them.

The decisions that matter

A modern Renaissance, if it is underway, will not be driven by questioning what to back, what to protect, what to ignore and what to build for the long term, when short-term sights are distorted. The question, then, is not when this era will eventually resolve itself, but whether those with the capacity to shape capital, culture, and institutions recognise what this moment is asking of them.

And the bigger question of all: what role do we play in making this happen?

The Wallace Collection

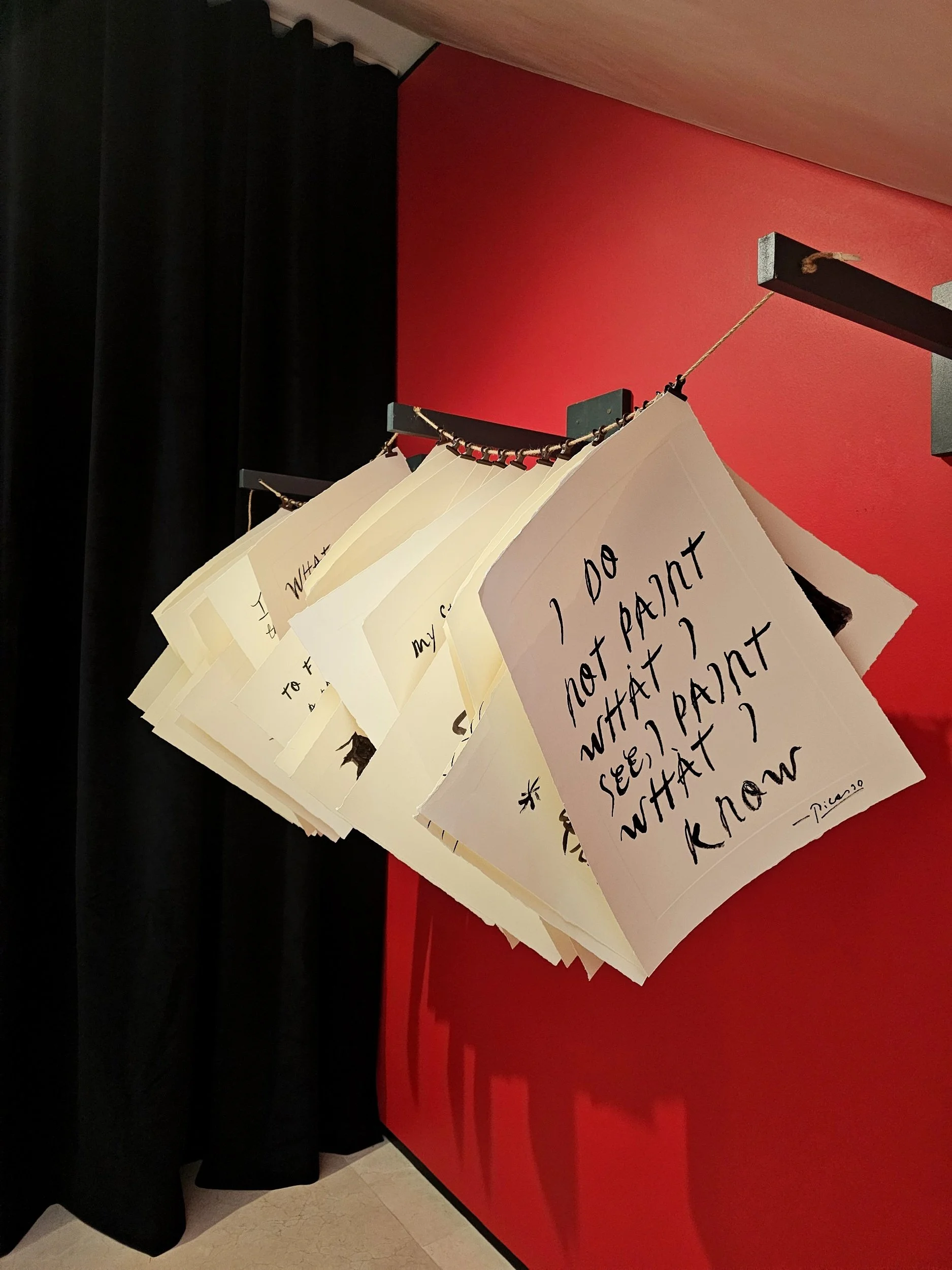

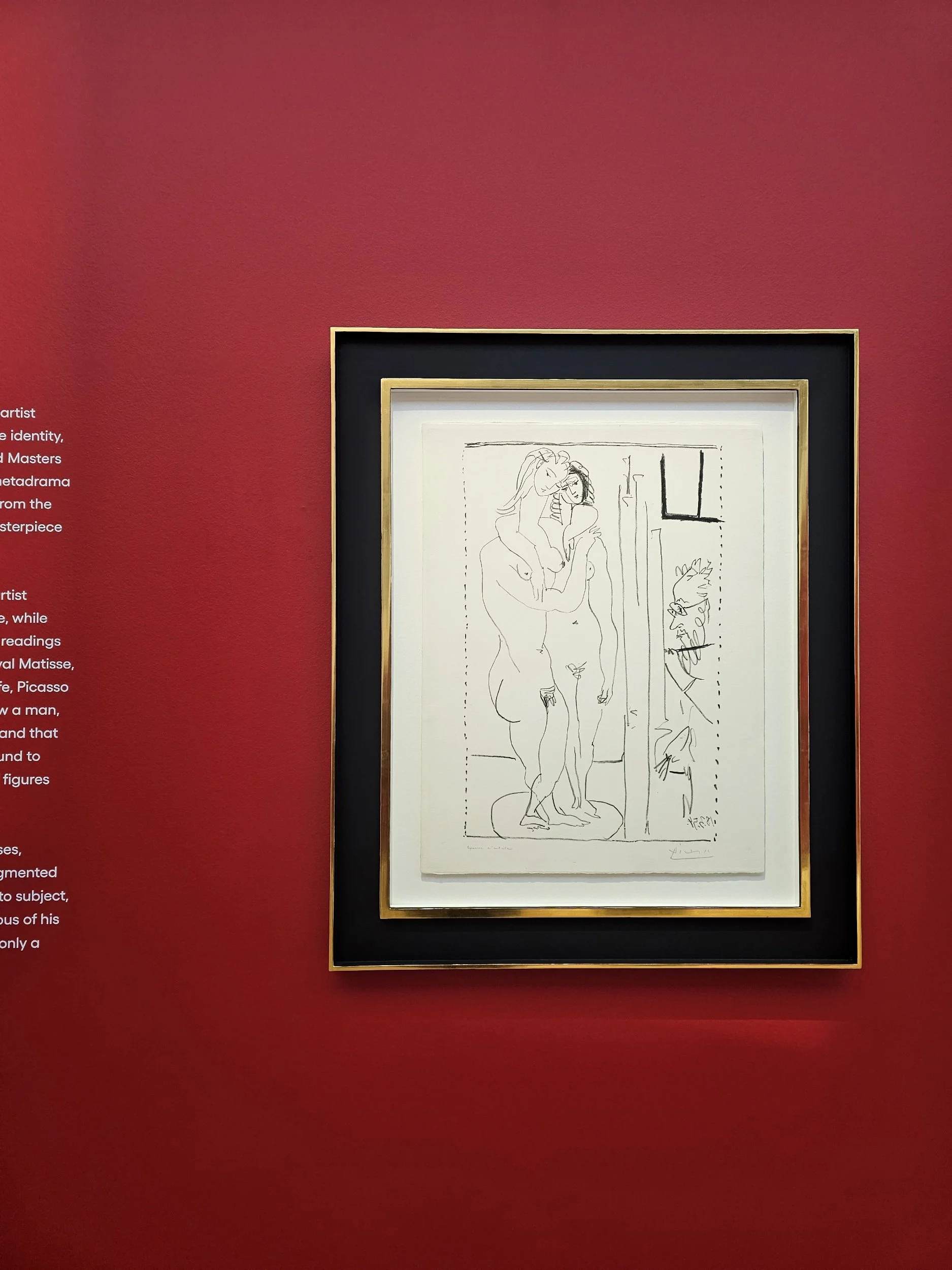

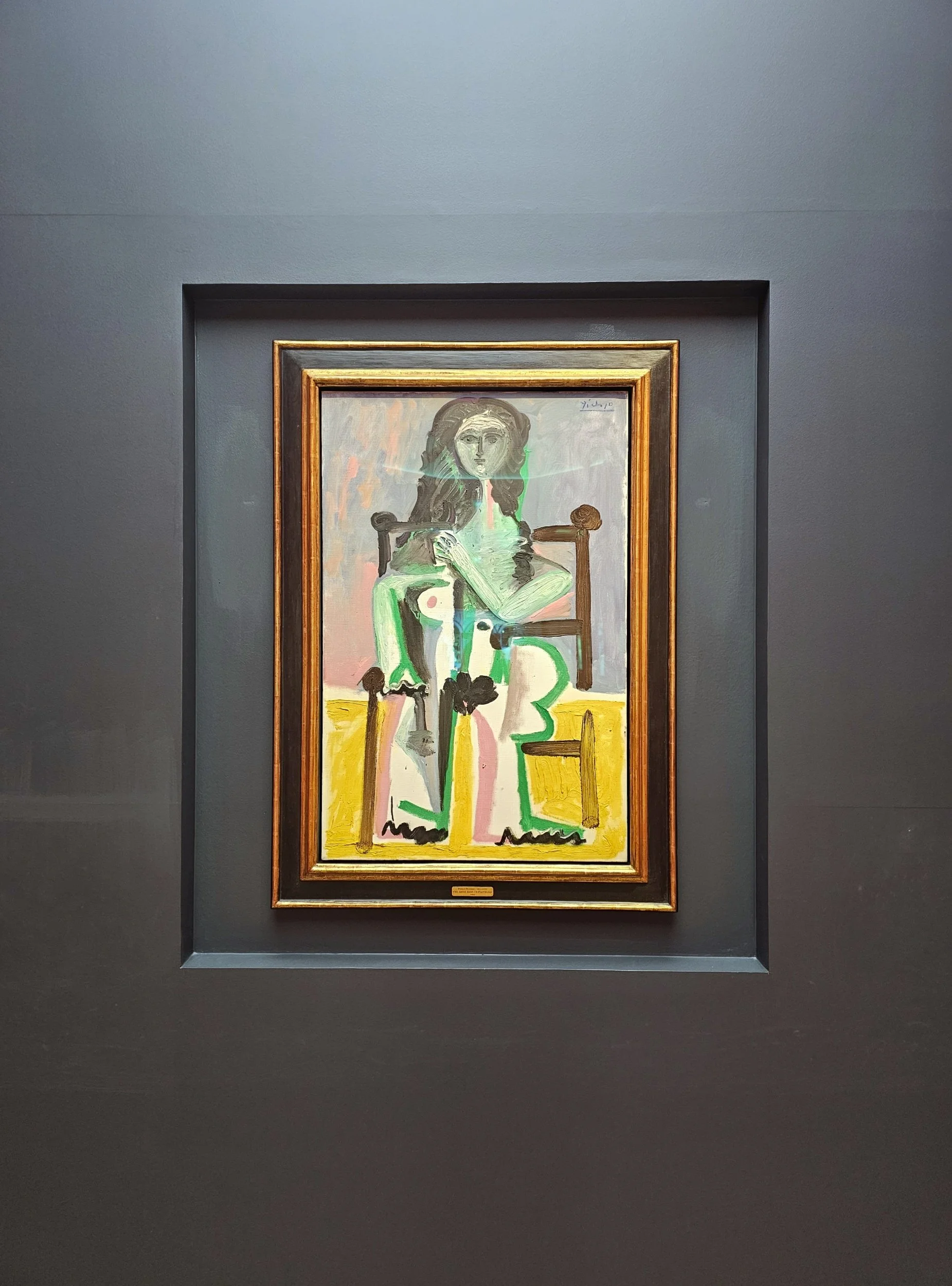

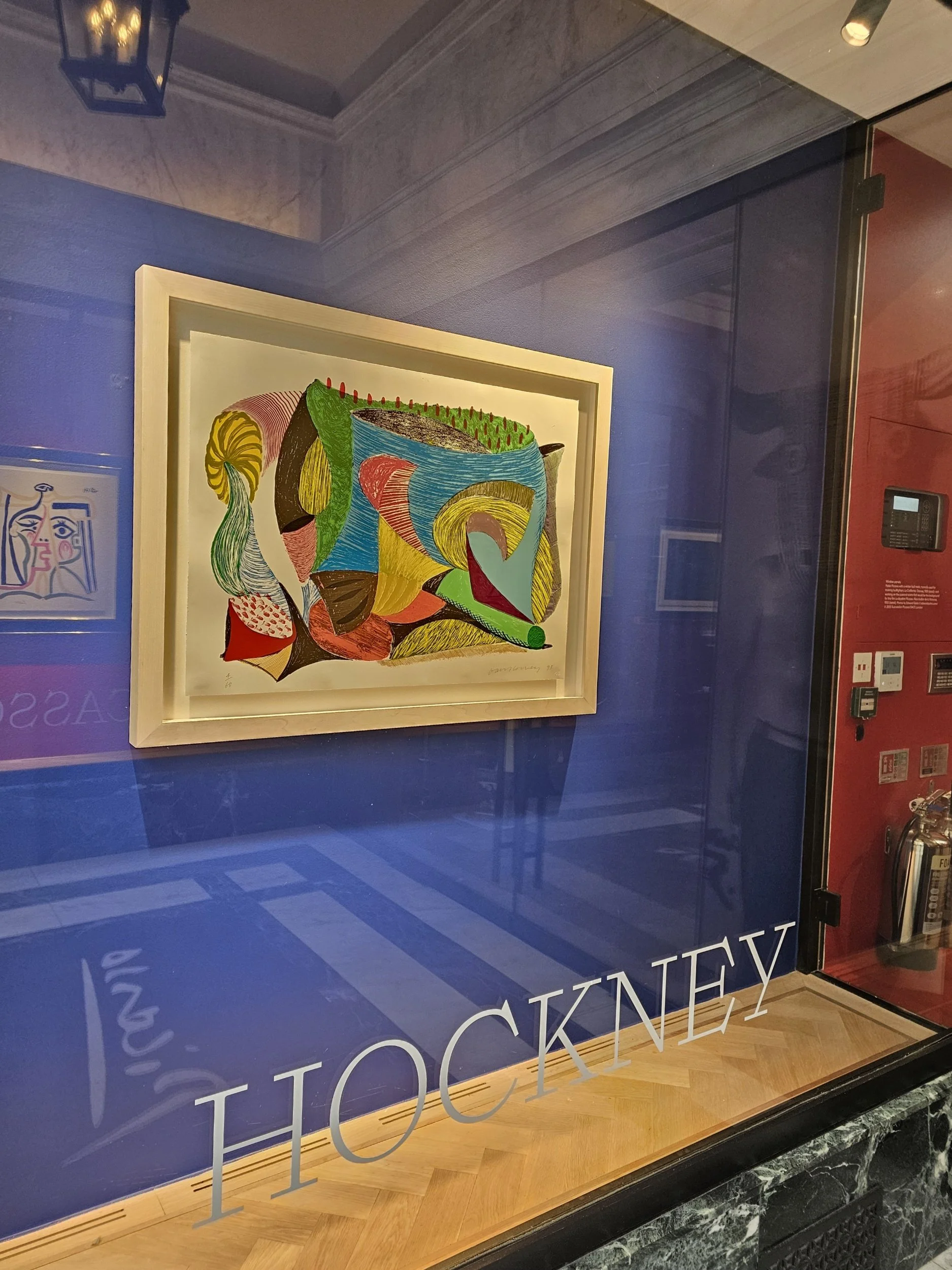

The Halcyon gallery

xxxx